In the second part of this article series, we are going to explore what shielding of APIs connected to mobile apps actually means. To provide some context, we will also look at how the bad guys approach attacking the APIs that connect with your mobile apps.

Shielding Right

In the media there is a lot of wise advice about ‘shifting left’, meaning ‘doing more work to improve our API security at development time’. That's all well and good but it's primarily focused on getting vulnerabilities out of your apps and APIs themselves. It doesn't per se prevent you from experiencing API abuse with, for example, the credential stuffing attacks we discussed in part 1. We like to call the runtime protection that's required to block API abuse through scripting ‘shield right’; in other words place a shield around your APIs to protect them. As previously described, this means making sure your APIs are being called from the correct context.

Image source: www.approov.io

Image source: www.approov.io

The key point to remember here is that you should have a regular and ongoing program to identify and fix vulnerabilities in your APIs, but in parallel you must also protect your platform from scripting attacks which may be attempting to abuse your APIs or to exploit existing vulnerabilities in them. So, both ‘shift left’ and ‘shield right’ are required.

API Security: The Hacker’s Viewpoint

Image source: www.approov.io

Image source: www.approov.io

If we think of the type of system we're trying to protect here, as shown above, we have a mobile app with a user and that mobile app probably has an API key in it. The user themselves will also have some kind of credential and this is communicating with the back end API service using TLS, i.e. the communication is encrypted. Traditionally we tend to think that the attack surface is the API itself and that might be protected by a web application firewall, API gateway or it might be sitting behind a CDN. If so then we have all sorts of technologies which can be used to protect the security of the user in terms of username and password, and the transformation of those credentials into OAuth2 tokens. Biometrics may also be used. Essentially the security of the service is delivered by checking that the user is authorized and that an API key is presented by the mobile app; if both of these check out then access to the backend resources/services is granted and WAFs, API Gateways and CDNs can do this.

Image source: www.approov.io

Image source: www.approov.io

To understand what might be wrong with this setup, let’s think about what an attacker might do if they are trying to find ways of exploiting vulnerabilities in the API or thinking about ways to abuse the API through scripting. They would go through the process of studying the mobile app’s code and its behavior when used. Obviously one of the challenges with a mobile app is that it is in the public domain and anyone can download it and analyze it. By definition therefore, any code used to access that back end service has to be in the app and is therefore more or less accessible to an attacker.

In many mobile services it's easy for a user to sign up. Typically the hacker will sign up with some anonymous email address; with these user credentials they can use the mobile app to access the service. There are a whole plethora of different tools that you can use to actually unpack what is inside the mobile app code. There are various reverse engineering tools available for both Android and iOS, e.g. APK tool, JADX which does Java decompilation, Hopper that does disassembly on iOS. There are various static analysis tools which look at the contents of the app itself and can extract secrets from the app. For instance, if there is an API key inside and it's not very well protected then it's relatively easy to extract. It’s also possible to take an app, reverse engineer it, and then make modifications and republish the app. You can then run it on your device with those modifications which will result in different functionality but will still be able to access the API while remaining undetected by your WAF/Gateway/CDN. That's only one of a number of avenues a hacker might take.

Image source: www.approov.io

Image source: www.approov.io

Another approach an attacker might use is where they have control of the device that they're running on and therefore they can use rooting and jailbreaking tools. There are many of these, e.g Magisk on Android, enabling rooting of a large number of different devices. There are also many iOS jailbreaks available now, covering a multitude of different iOS versions. Once jailbroken or rooted, a device is completely under control of the attacker.

That level of control enables the installation of various hooking and instrumentation frameworks which allow hooking of chosen functions inside a genuine instance of your mobile app which is running on the device. In this way the attacker can see the data that is being passed into and out of the mobile app. In fact there are even scripts available that hook at the http transfer level in order to see all the transactions that are occurring between the mobile app and the back end API. The user interface allows the attacker to see how the data is being generated. So, even if there is some level of obfuscation or hardening in the mobile app code, it is still possible to get a dynamic picture of what type of calls the mobile app is making and what kind of credentials it's passing to the back end API in order to make those accesses.

Image source: www.approov.io

Image source: www.approov.io

The final approach that attackers might use is to insert themselves in the channel itself. Even though the channel is encrypted between the mobile app and the back end service, that doesn't prevent a hacker - especially if they have a jailbroken or rooted device - from becoming a man-in-the-middle within that channel.

To achieve this, they will use a tool like HTTP Toolkit, which sits in the channel between the mobile app and the back end API. Once done, the mobile app will think it's talking to its server, and the server will think it's talking to the mobile app. However, what is actually going on is that the hacker is using a self-signed certificate that they have pushed onto the mobile app so it starts to trust the channel even though it's actually communicating with the man-in-the-middle (hacker).

The advantage that the hacker now has is that they can see all the traffic going between the two ends of the channel, can capture the traffic, can replay the traffic, and can of course modify the traffic. Poking around with an API is where an attacker will usually start. Following this investigative work, the attacker could capture some real transactions from a mobile app, then try modifying the transactions to search out BOLA vulnerabilities by modifying resource IDs and/or user IDs as discussed in part 1 of this series.

One of the protections against man-in-the-middle attacks is to pin the connection between your mobile app and your API endpoint. This technique locks down the mobile app so that it will only trust certificates from the service you're trying to connect to even if an additional trust anchor certificate has been pushed onto the device. Depending on how the pinning has been implemented, on a rooted or jailbroken device it can be defeated, but in spite of that, we do recommend mobile channels are pinned. We have written extensively on this topic and for more information, please check our “how to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks” whitepaper, or the recording of a webinar we did on this subject.

In summary then, from a hacker's point of view, the steps to executing an attack are:

-

Reconnoiter

- Understand the backend service from static and dynamic analysis (break open the mobile app to analyze its code, analyze its dynamic behavior using instrumentation tools, analyze the traffic using a proxy, try to understand what it's doing try and understand the shape of the API)

-

Weaponize

- Build a script that impersonates the app or;

- Build a modified fake app or;

- Hook and control the original app

-

Attack

- Explore/exploit vulnerabilities in the backend API or;

- Run a credential stuffing attack against login endpoints or;

- Run bots to abuse the APIs and business or;

- Distribute a modified app to real end users.

The Mobile Attack Surfaces

Image source: www.approov.io

Image source: www.approov.io

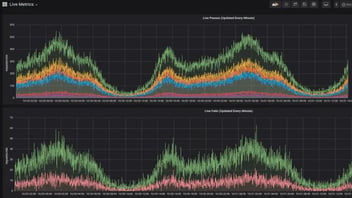

Referring to the image above and summarizing the holistic view of the mobile channel threat landscape we have been discussing, we started off looking at the vulnerabilities in the service or the vulnerabilities in the API itself (attack surface 1 above). We also noted that there are other attack surfaces we need to worry about as well, especially when considering API abuse. There is the attack surface of the integrity of the channel - are the requests that are coming from the mobile app being modified or monitored in any way (attack surface 2)? Then there's the attack surface of the app itself - is the app actually the app you think it is or has it been modified (attack surface 3)? Next we need to think about attacks on the device that the app is running on (attack surface 4). Finally there are attacks against the user credentials either because somebody with the intent of hacking the API has signed up as a user or because leaked data is being used in some kind of credential stuffing attack against the back end API (attack surface 5).

In this second article of the series, we’ve looked at what API shielding and how it relates to the threats outlined in part 1. We’ve also looked at securing mobile-centric businesses by getting inside the head of an attacker to appreciate the breadth of approaches available to them. In part 3 of the series, we will look at the essential elements of shielding an API and how you should set about implementing best practice.

Contact us to leanr more about our mobile app protection service.

David Stewart

Advisor at Approov / Former CEO of Approov

30+ years experience in security products, embedded software tools, design services, design automation tools, chip design.